Uncovering what lies beneath our cities – all with our internet’s optical fibres

From ensuring our homes don’t crack to keeping our skyscrapers standing tall – understanding our city’s bedrock is foundational. Our researchers are repurposing the optical fibres already buried beneath Melbourne to map what lies beneath – all without digging a single hole.

The challenge

“Thumper trucks” and in-ground sensors every 4-metres – standard technologies are too invasive for cities

To keep our city’s infrastructure in good health, we need to monitor what’s happening beneath our urban environments.

However, current methods for assessing ground structure beneath busy roads, buildings and footpaths are invasive and impractical – often requiring large ‘thumper trucks’ or sensors buried every four meters.

Another technique called Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) repurposes our existing internet’s optical fibres – which are very sensitive to vibration – and turns them into cost-effective, ground motion sensors that can then be used to map the subsurface.

But in a dense urban environment, how do you get access to these optical fibres to better understand what lies beneath?

COMBS seismologists connected specialist lasers to 'dark fibre' to create a detailed picture of the Melbourne's underlying bedrock

Our response

Tapping into a 76-kilometre underground testbed – without disturbing the city above

Running from RMIT University to Melbourne’s east and Monash University is a 76-kilometre loop of ‘dark fibre’- optical fibre not used for everyday internet traffic, but put aside for collaborative research.

This underground lab – the Australian Lightwave Infrastructure Research Testbed (ALIRT) – makes up a very small portion of Melbourne’s existing optical fibre network.

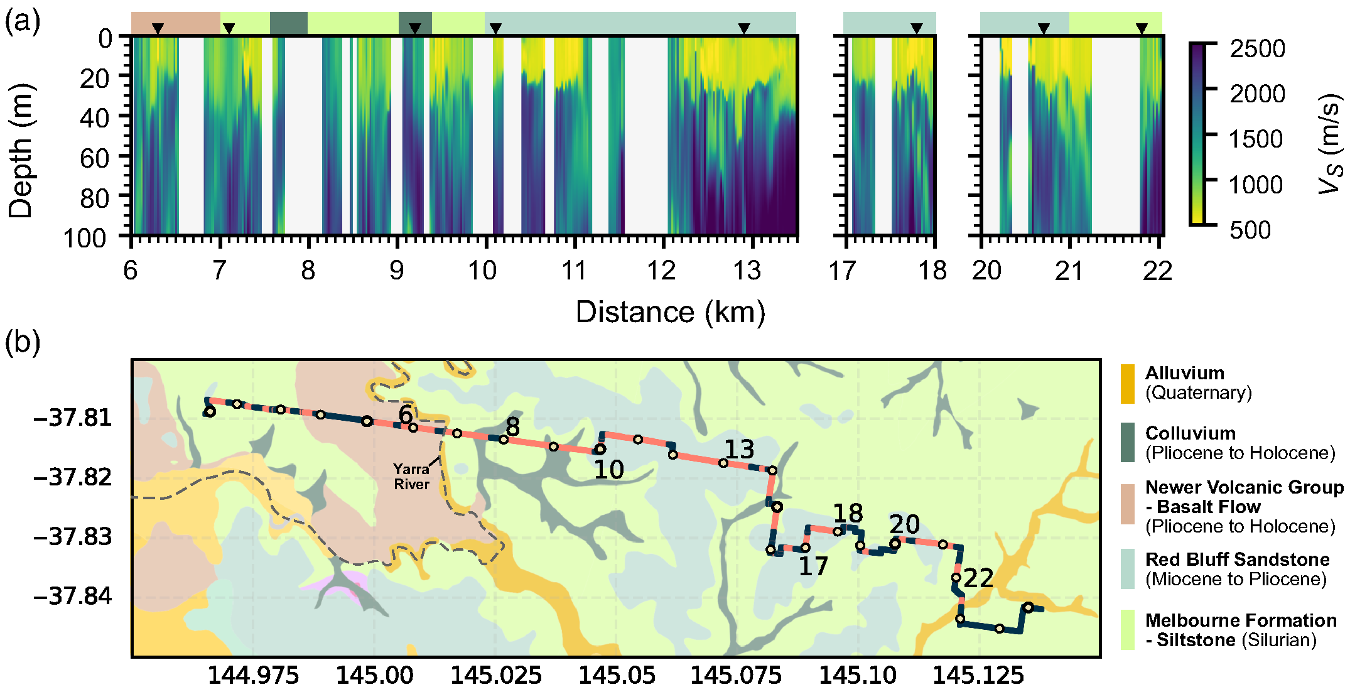

Our seismologists, Associate Investigator Voon Hui Lai and Chief Investigator Meghan Miller, connected a specialised laser to part of the fibre and ‘listened in’ to Melbourne’s traffic, trams and even river flows – capturing vibrations to create a detailed picture of the city’s underlying bedrock.

The results and current progress

Turning the hum of Melbourne’s traffic into a tool for seismic imaging

With the testbed of dark fibre, Voon and Meghan developed a model that used the background hum of the city – trams, trains and traffic – as a ‘light source’ to see 10 metres beneath Melbourne’s concrete jungle.

This revealed bedrock and soil types at metre resolution – distinguishing sandy, silty or volcanic layers. This precise map can help engineers predict how areas might respond during earthquakes: softer soils like alluvium amplify shaking, and dense bedrock, like bluestone, absorb it.

Our COMBS researchers are now working to use our microcombs to sharpen this resolution, improve signal clarity, extend the technique to remote and underwater areas, and streamline data processing for real-time seismic monitoring.